Chris Pruett, Meta’s Director of Games and head of Oculus Publishing, held a fascinating talk at the Game Developer Conference 2025 that covered everything from developers’ frustrated “theories” about plummeting Quest sales to his predictions for the next big customer base for the (unannounced) Meta Quest 4.

The Meta Store shift prioritizing Horizon Worlds and emphasizing popular free-to-play content has frustrated plenty of developers, some of whom held a separate GDC 2025 panel this week on “Solving VR gaming’s visibility crisis” and directly addressed how Meta’s policy changes made the Quest Store a non-factor for visibility and viable profits.

I attended both this panel and Pruett’s “The past, present, and future of developing VR and MR with Meta,” and the latter’s presentation felt like a direct response to the developer angst sweeping the industry.

“A number of developers have told us that their revenue is declining, that they are worried about their reach, and that the changes we’re making to our platform are impacting their businesses,” Pruett said.

He then broke down how Meta’s internal data compares against the “theories” about Meta’s policies with the Quest Store, Oculus Publishing, and Horizon Worlds, including how the Quest 3 and Quest 3S audience spends its money and how developers should break through the “meme game” dominance of the past year.

Oculus Publishing isn’t going anywhere

Meta’s Oculus Publishing initiative led to 100 new games in 2024, but the $50 million Horizon Worlds creator fund has led to criticisms — including from my colleague Nick Sutrich — that Meta isn’t prioritizing traditional developers anymore.

Pruett responded that they still have 200 titles in active development through Oculus Publishing. They also are funding 21 developers through the Ignition program, which they announced at GDC 2024 to support laid-off developers.

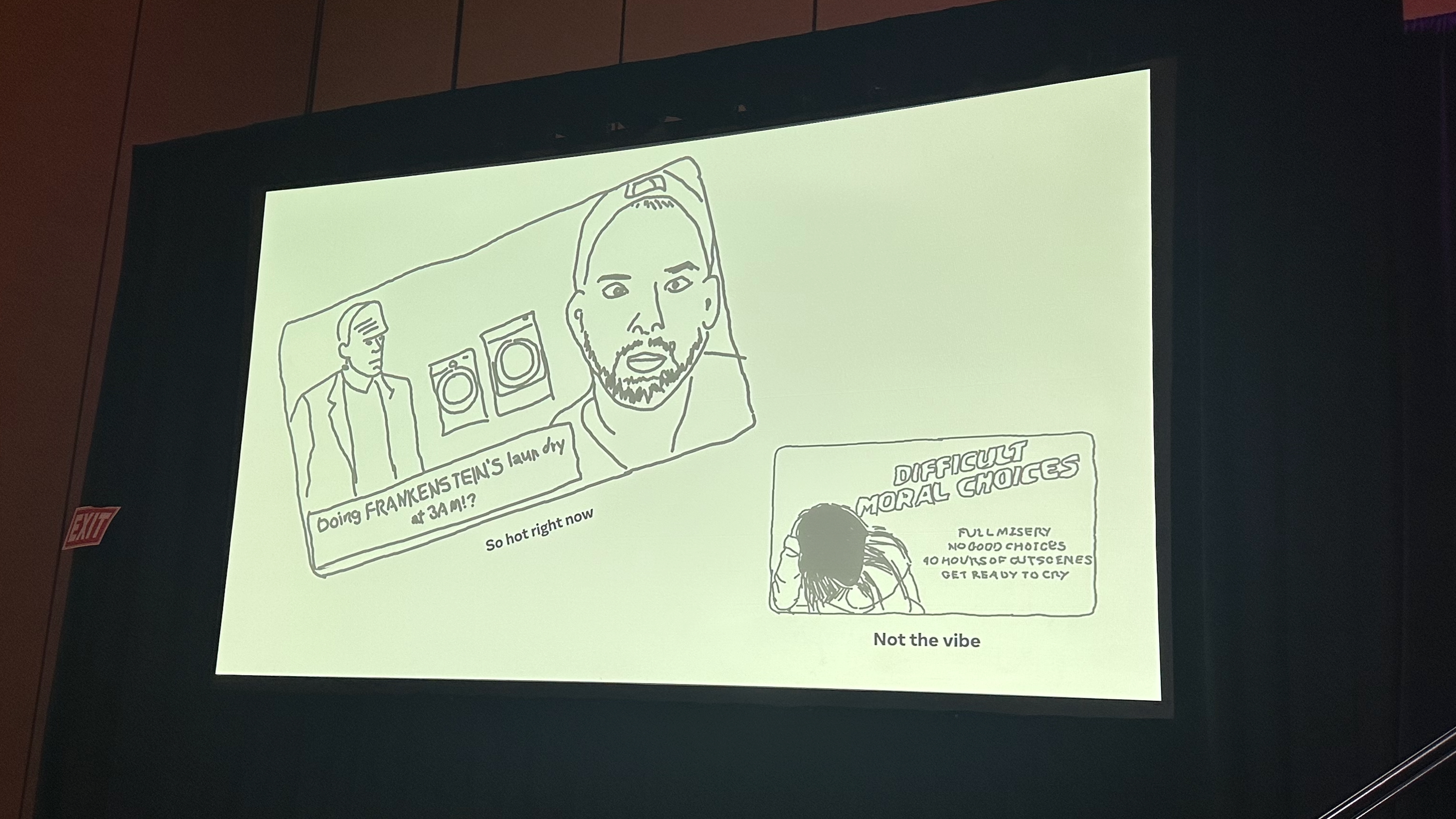

He did admit that Oculus Publishing is now looking for a “very different” type of content targeting new audiences — more on that later — but as the head of content for the biggest VR platform in the world, Pruett used his GDC 2025 platform to reassure developers that they shouldn’t assume the Meta money well has dried up. Nor should they feel forced to target teens.

Gamers don’t use the Quest Store to decide how to spend money

Other “theories” Pruett set out to debunk at GDC were that Meta had shifted its priorities from paid apps to free-to-play in-app payments (F2P IAPs) or that revenue had fallen because Meta opened up its store to App Lab titles.

Pruett said they did a substantial “data analysis” to determine the shift in its users’ purchases. They found that most users buy a ton of games after they first unbox their VR headset but then never return to the Quest Store to browse, except when “off-platform advertising” draws them to one specific title. Store placement doesn’t matter, except in the peak moments like Black Friday and Christmas when Quest activations spike.

Teens are more active Quest users year-round, but they’re much more “price sensitive” and, like adults, tend to let external sources like streamers, influencers, and friends dictate what they’re willing to try.

Overall, Pruett said, “paid apps are still the majority of our revenue on the platform by an overwhelming margin.” F2P IAPs have steadily climbed, but they’re not necessarily stealing money from customers who used to buy critically acclaimed Quest titles. Instead, the old VR guard isn’t spending as consistently as it used to, and the new customer base skews younger and prefers “meme games” to emotional AAA titles.

He pointed to internal Meta data that the opened app store and Horizon Worlds push in the mobile app decreased Quest Store profits by “<1%” and “3%,” respectively, while overall store profits climbed by 12% in 2024. So, in Pruett’s mind, the impact of these changes was “very small,” even if individual developers saw declines.

I did, in hindsight, find Pruett’s argument flawed. Turning the Quest Store from a curated experience into a free-for-all Steam-like that prioritizes Horizon Worlds obviously impacted some developers; the fact that new developers have swept in to claim record profits doesn’t refute the fact that other games that would once have stood out are now instantly buried.

Opening up the Quest Store was the right decision to find fresh indie content for a younger audience. But Pruett’s analysis doesn’t consider the reason why older VR gamers aren’t coming back to the Quest Store after unboxing their Quest — presumably, because it’s overwhelmingly bloated and because the top-selling titles skew towards the teen audience.

Meta does recognize this fact, even if it doesn’t take ownership of developers’ struggles. It’s hiring more people to improve the Quest Store, improving personalized recommendations and game filter options, and revamping game pages to allow devs to share user-generated content and social media posts.

For now, though, Pruett’s talk makes clear that developers need to find alternative ways to reach audiences, not simply hope they stand out by quality and old successes.

During the Q&A, I asked Pruett if Meta is seeking alternative marketing methods outside of the Quest Store or if developers need to do this themselves. He answered that he sees Meta’s biggest job as “increasing the amount of time people spend in the headset.” Developers have a “much stronger lever” for keeping users invested in specific titles, but they need to look for alternatives to traditional Quest Store discoverability or buying ads.

The “big spikes in success” that many devs saw came “because they went viral on TikTok or on Instagram,” Pruett said, and he thinks devs are “underleveraging” this resource.

He also pointed out how the devs behind games like Gorilla Tag and Animal Company have done a great job of building and managing a “robust community” on platforms like Discord, which allows them to pull users back into their game any time they announce an update.

The next big audience for VR and Quest, according to Pruett

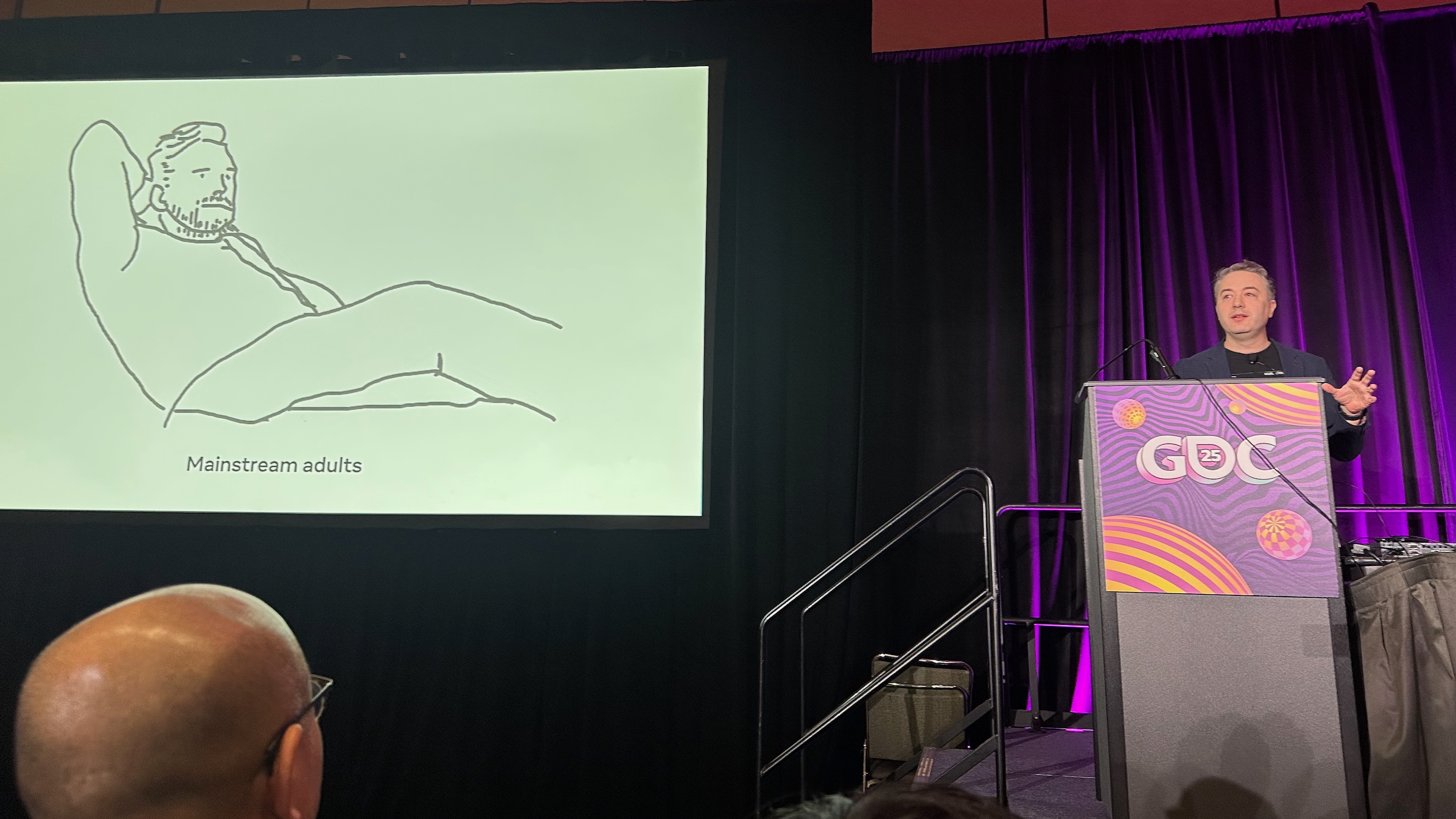

Pruett’s talk ran through the different demographics of VR gamers who bought Quests over the years, from PC VR power users to “VR Elites” who bought the Quest 2 and 3, ending with the current youth influx via the Quest 3S. These groups aren’t going away, but Meta’s internal data suggests a new demographic will grow substantially on Quest in the next few years: “mainstream adults.”

For this group, Pruett says, gaming is a “secondary pastime.” These “30-something dads” will see Meta Quest as a “really high-end TV.” And “as the resolution of [Meta’s] devices increases,” using a headset as a TV replacement becomes more “viable.”

While this group is small now, Meta predicts that by 2027, mainstream adults will be the next “major player” on Quest after the teen influx. That’s why Pruett said developers shouldn’t pivot to teen games to join Oculus Publishing. Instead, they want developers to start making content now for the “mainstream” non-gamer crowd in a couple of years.

I found this fascinating for one obvious reason: several leaks point to the Meta Quest 4 shipping in 2026. If Meta wants to court this new casual-streamer dad group, then I’d be shocked if Meta didn’t try to boost the Quest 4 resolution enough to make it tempting as a TV alternative. Either that or try and make it light enough that it’s more comfortable to wear for a 2-hour movie streaming session.

Speculation aside, this talk made it clear that Pruett wants to debunk the idea that Horizon Worlds, Gorilla Tag, and traditional Quest games can’t co-exist.

“Our commitment to continuing to grow the ecosystem is unwavering, but we’re learning in real time,” Pruett said. He urged developers to get in touch with Meta and share their experiences and expectations, and he remained optimistic that the Quest space will continue to evolve and grow — not just become a kid-dominated space where some devs can’t profit.